It’s been a year rife with developments—some hopeful, some extremely alarming—for the fight to end HIV and the state of LGBTQ+ civil and medical rights. Avita Care Solutions Chief Advocacy Officer Glen Pietrandoni invited Vice President of amfAR and HIV health disparities expert Greg Millett to chat with Avita team members about the current research, policy, societal climate, and his predictions for what to expect moving forward. Read on for an edited transcript.

Glen: Thanks so much for joining us here today, Greg. It’s an honor to have you chat with our team about where we stand in the fight to end HIV and what impact recent attacks on the LGBTQ+ community are having on America’s goal to do so by 2030.

Greg: It’s a pleasure to be here with a group of people doing so much to help the LGBTQ+ population, particularly maintaining their health and getting the U.S. toward our final goal of ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic. I’ll give you all an overview of where we are in terms of not just the fight to end HIV but also how the rights of the LGBTQ+ community are faring in the U.S., which are interlinked.

I look at the current situation as a "two steps forward, one step back” scenario because many things are happening right now that mitigate our efforts to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Greg Millett, Vice President of amFAR

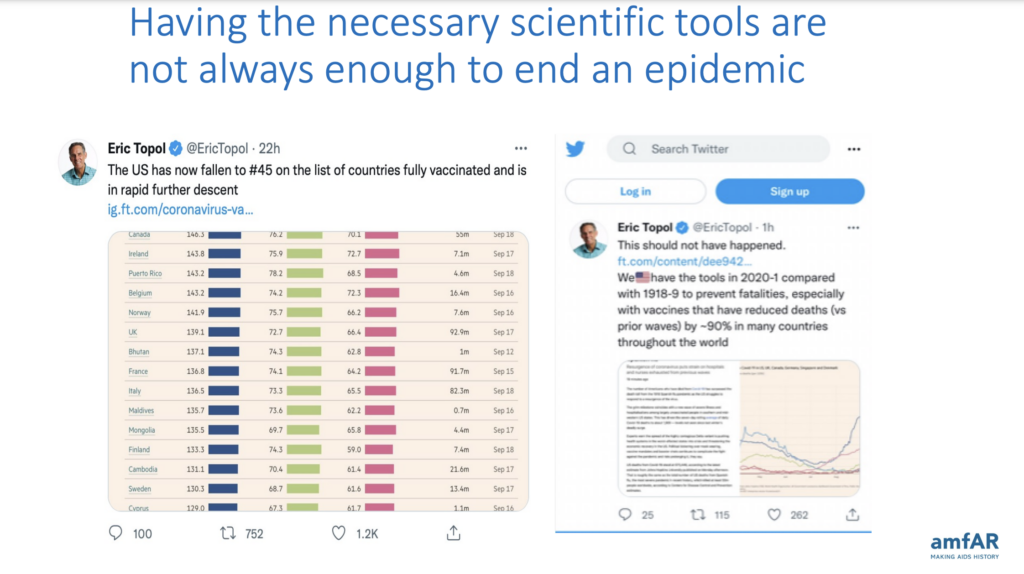

I look at the current situation as a “two steps forward, one step back” scenario because many things are happening right now that mitigate our efforts to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic. I’ll start with insights from Dr. Eric Topol, one of the major scientific voices throughout the COVID-19 pandemic.

Dr. Topol was incredibly excited when we got COVID-19 vaccines approved, and he thought we would end the pandemic quickly. But as we all discovered, even though we had the tools to end the epidemic, the U.S. quickly fell far behind many other Western industrial nations in vaccinating most of our population for COVID-19.

Dr. Fauci also said that we have the tools to end the HIV/AIDS epidemic—and I agree by and large—but we also have to be mindful of other mitigating factors that make it more difficult for us to do that. And unfortunately, in the last couple of years, we’ve seen that in full force.

Attacks on LGBTQ+ rights create a “dystopian universe”

Glen: Tell me more about the mitigating factors hindering our fight to end HIV.

Greg: The data consistently shows that 60-66% of new HIV infections in the U.S. occur among the LGBTQ+ population. And in the past year alone, we’ve seen a huge increase in attacks against this community. Gender-affirming care is being banned for youth, with the HRC (Human Rights Campaign) now estimating that up to 45% of trans youth will not have access to gender-affirming care.

There were 417 anti-LGBTQ+ bills introduced in the first quarter of this year alone, and legislators signed 75 of those into law. We’ve seen a 1000% increase in book bans over the last year, and perhaps it’s not a surprise to learn that over half of the banned books are LGBTQ+ focused.

You know we’re evolving into a dystopian universe when a Florida teacher might lose her job because she showed a Disney movie with a gay character to kids.

GREG MILLETT, VICE PRESIDENT OF AMFAR

And then, of course, we’ve got the proliferation of “Don’t say gay” bills nationwide. You know we’re evolving into a dystopian universe when a Florida teacher might lose her job because she showed a Disney movie with a gay character to kids. The transgender population, in particular, remains incredibly vulnerable. When you look at the polls, nearly half of Americans believe we’ve gone too far in accepting trans people.

The connection between stigma and sexual health

Glen: How are the violation of LGBTQ+ rights and our nation’s work to end HIV connected?

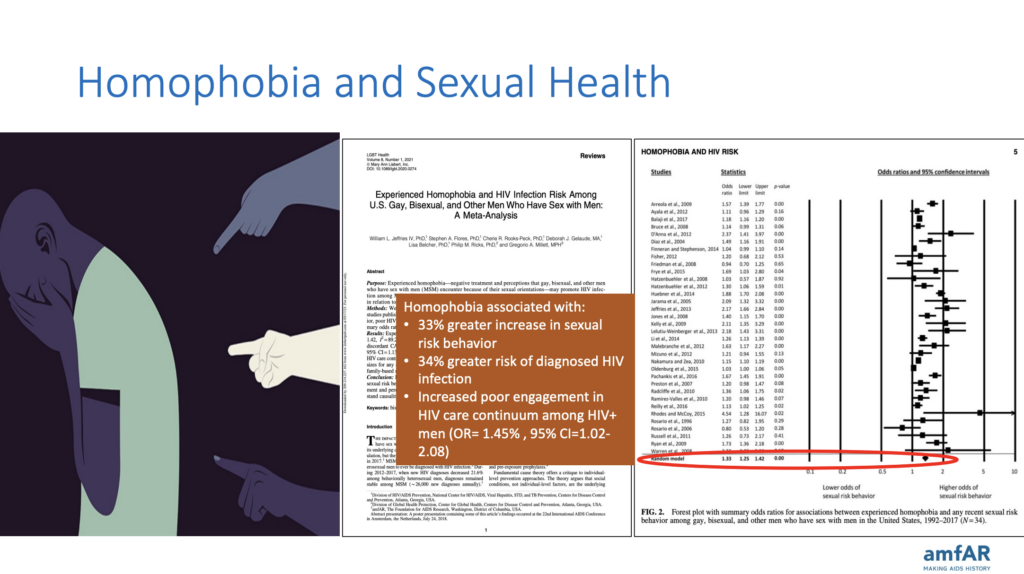

Greg: It all has ramifications. We’ve seen a lot of data about how homophobia and stigma affect depression as well as suicidal ideation among LGBTQ+ youth. But there is also a connection between stigma and sexual health. I published a paper a couple of years ago with my colleagues at the CDC (Centers for Disease Control), where we looked at stigma’s impact on sexual health for gay and bisexual men. We found that there was a 33% greater increase in sexual risk behavior for those men who said that they experienced stigma. There was a 34% increase in diagnosed HIV infection among those who experience stigma. And among those men who are HIV positive, there was poorer engagement in care across the continuum for those who experienced stigma.

So, it’s clear that these anti-LGBTQ+ actions taking place across the nation (like the anti-trans legislation, ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bills, etc.) will have huge consequences on our ability to end HIV/AIDS in the U.S if, as the data shows, stigma itself helps to fuel HIV infection. The CDC just released a report a couple of weeks ago showing there have been some slight declines in new HIV infections in the U.S. Given [the anti-LGBTQ+ initiatives] taking place now, we’re probably going to see those declines halt, and we might see some increase in the infection rate.

“An existential moment” in the fight to end HIV and secure LGBTQ+ rights

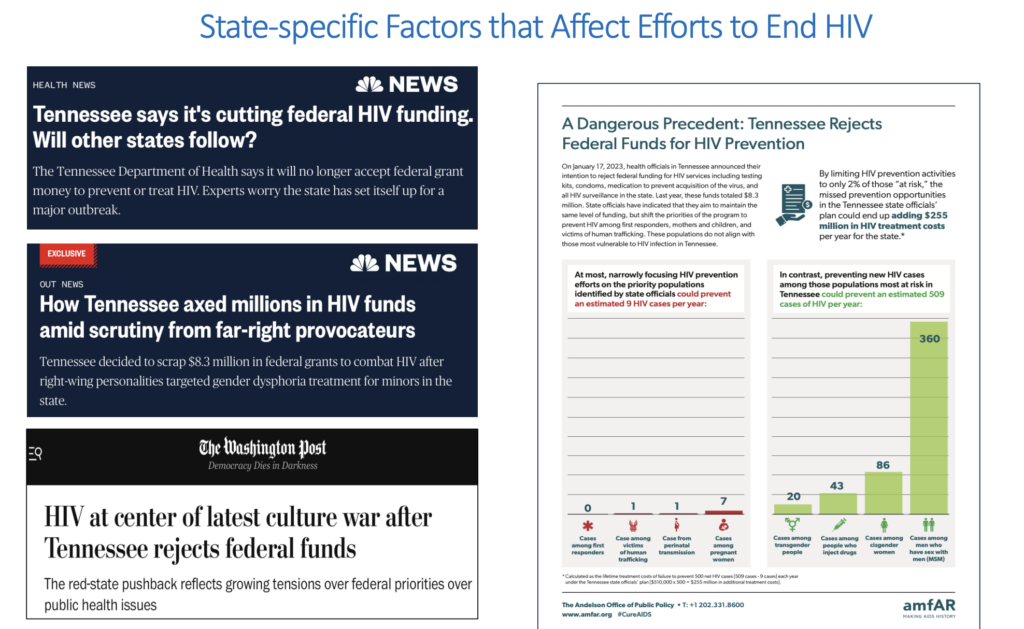

Glen: Let’s talk about the impact of specific state actions, such as the State of Tennessee rejecting nearly $9 million in federal funds to prevent and treat HIV.

Greg: A lot of [the rejection of these funds] is precipitated by an aversion to taking funding for trans populations in Tennessee, as well as Planned Parenthood. My colleagues and I at amfAR pulled together an infographic to take a look at what the ramifications of this might be. Instead of funding the populations proven to be at the highest risk of HIV, Tennessee said they would fund the populations they believed were at the greatest risk. This included first responders, pregnant individuals, and a few other groups.

This is an existential moment for the LGBTQ+ community, particularly for our efforts to fight HIV.

Greg MILLett, Vice President of Amfar

But when we looked at that initiative and compared it to Tennessee’s surveillance data over the past 15-20 years, we found that the groups the state wanted to focus on only comprised about nine HIV cases each year, compared to the groups we know are at greatest risk, which are primarily men who have sex with men and the trans population. By focusing just on 2% of those at risk in Tennessee, the state will end up increasing infections each year, which could total well over $200 million in HIV treatment costs alone.

And it’s not just the policy issues in Tennessee. The Braidwood vs. Becerra decision could potentially halt people’s access to affordable preventative care like PrEP. Researchers at Yale looked at Braidwood and said it could cause an increase of 2000 HIV cases in the first year alone. This is an existential moment for the LGBTQ+ community, particularly for our efforts to fight HIV.

A game of infectious disease “whack-a-mole"

Glen: How does HIV/AIDS interact with other infectious diseases on the radar in the U.S.?

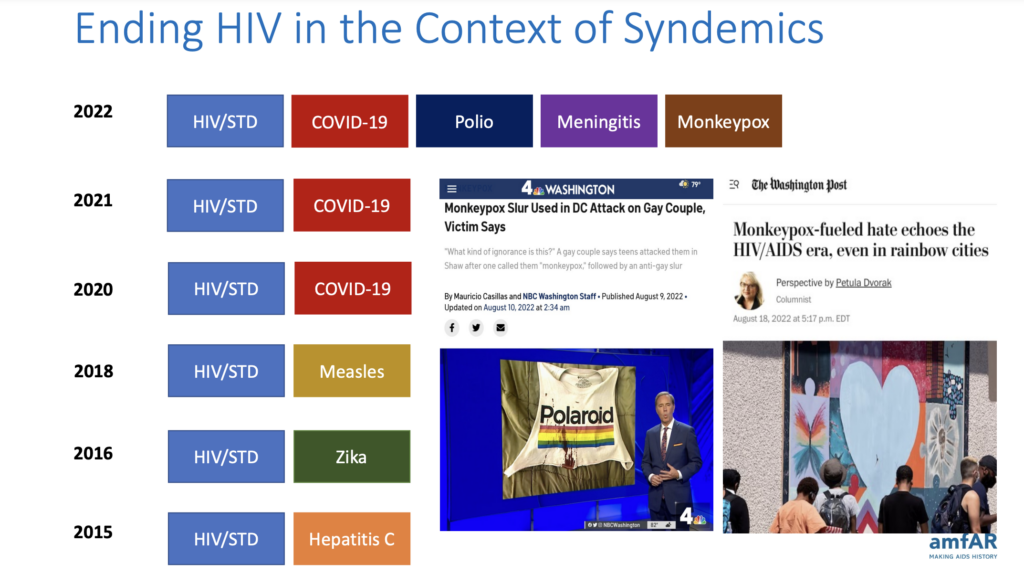

Greg: We’ve been dealing with a confluence of many infectious diseases over the past several years. We call this a syndemic or the overlapping of infectious diseases. In 2015, it was HIV, STDs, and Hepatitis C outbreaks. In 2016, there was the Zika outbreak. In 2018 came the measles outbreak. And, of course, 2020 and 2021 broke the paradigm in terms of infectious disease outbreaks with COVID-19 worldwide. In 2022, it was essentially just whack-a-mole with infectious diseases, including COVID-19, polio, meningitis, and monkeypox. Three of those primarily affect gay and bisexual men, so there was the risk of even greater stigma.

Celebrating diversity as a means to an end to HIV

Glen: Is there any good news?

Greg: Several developments are hopeful signs. One is the visibility of LGBTQ+ people in federal positions, particularly at the White House and HHS (Health and Human Services). It’s terrific to see a range of LGBTQ+ individuals in positions of power in Washington, DC.

The Protection of Marriage Act is also important. We’re seeing that LGBTQ+ populations overall are far more accepted by the American public than at any other time in history. It’s much harder to demonize us when upwards of 71% of Americans believe same-sex marriage should be legalized. Many of us in the LGBTQ+ community, particularly those of us who are older, didn’t think this was a remote possibility back in the 80s and 90s. To see where we are today in terms of acceptance is remarkable.

The U.S. is just a qualitatively different country from 45 years ago. That’s something we should celebrate. It’s a trend we’ll eventually prevail upon, and it will help us end the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

greg Millett, vice President of amfar

Epidemiologists are anxiously watching the surveillance data

Glen: Regarding the CDC data that just came out showing lower infection rates, do you think that’s a function of lower testing rates during the COVID pandemic? Taking it to the next step, how does that contribute to our nation’s goal of ending the epidemic?

Greg: When they released that data, the CDC cautioned against our overinterpreting what we see in those trends, whether it’s a true decrease or not. There are still aftereffects of COVID-19, such as people not seeing their providers as frequently as before COVID-19. And given what’s taking place with other dynamics in the U.S., like the anti-LGBTQ+ legislation, we’ll probably get a more accurate picture of where we are with the surveillance data over the next few years. Instead of the HIV diagnoses going down, which I’m still not sure is taking place, we’ll probably see some increases again for LGBTQ+ populations, particularly for transgender individuals, gay and bisexual men, and gay and bisexual men of color.

Another thing that worries me is that we used to have successes we could point to in our HIV surveillance data for women and people who inject drugs. With some of the policy changes that are taking place right now, I’m afraid we won’t see those declines in diagnoses any longer, and we might start to see an increase in HIV diagnoses among these populations. Many epidemiologists are waiting anxiously to see the outcome of our checkered policy landscape, which could influence where we’re going with ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

Many epidemiologists are waiting anxiously to see the outcome of our checkered policy landscape, which could influence where we’re going with ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic.

greg millett, Vice president of amfar

Eye on the target: Ending HIV by 2030

Glen: Do you think we’re in trouble with hitting the nation’s goal to end HIV by 2030? What needs to happen to stay on target?

Greg: I think we can still make it. If we can get over this Braidwood decision and have long-acting PrEP available, as well as a wider dissemination of injectable ART (antiretroviral injection), that could go a long way toward ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic in the U.S. Also, 2030 is a while away. We’ll have a couple of different administrations, ostensibly, between now and then, and we need to make sure they are focused on ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic both domestically and globally. We also need to consider other known unknowns that will crop up and might delay ending the epidemic. For instance, we know that eliminating health inequities would drastically reduce the number of HIV infections.

Not as many people are interested in HIV these days. It’s not a cause that galvanizes people. We need to change that. One way to do so is with a proof of concept. If we can end HIV in a location like Boston, New York, or San Francisco, that’s something people can rally around. When that happens, people will pressure their lawmakers and say, “Well, if they can do it in that locality, why can’t we do it here?”

Not as many people are interested in HIV these days. It’s not a cause that galvanizes people. We need to change that.

greg millett, vice president of amfar

Seeing things clearly as a member of the HIV and LGBTQ+ community

Glen: Related to the article you wrote for The Advocate: How have your personal experiences informed your policy recommendations and the way you work daily?

Greg: I remember going to the White House after being at the CDC for 13 years and thinking, what do I have to do differently? One thing that moves policy, particularly in Washington, DC, is telling a story somebody can relate to. So, as soon as I got to the White House, I told my husband that I needed to let people know that while I publish in medical journals and speak at scientific conferences, I’m also HIV-positive and explain what that journey was like for me.

Doing that was incredibly helpful, not only in terms of gaining trust in the community but also in terms of my insights as a scientist. When you’re a community member, you can see things slightly differently. Certainly, my interest in doing work involving health inequities stems from being a Black Latino gay man from New York who saw many friends disappearing in the 80s and 90s.

Every time I returned from college, I’d see more and more friends who were sick or dying. To have that happen to you in your early 20s is shocking. I remember one time when my father was really upset. He was in his 40s, and one of his high school classmates recently passed away. It hit him hard. And I said, “Dad, I feel bad for you, but I don’t think you fully appreciate that I’ve had half of my friends pass away in the past three years alone, and I’m half your age.” That gave him pause to try and understand what was happening, and it’s a big part of why I’m interested in research and policy around health inequities today.

Certainly, my interest in doing work involving health inequities stems from being a Black Latino gay man from New York who saw many friends disappearing in the 80s and 90s.

Greg Millett, vice president of amfar

What’s your take? Whether you have an idea for a future guest or topic for our series or would like to comment on the insights of one of our past guests, we’d love to hear from you! Reach out to us at [email protected].

About Greg Millett

Greg is a vice president at amfAR, the Foundation for AIDS Research, and the director of amfAR’s Public Policy Office. He is a former CDC senior scientist in the Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention, and he also served as a senior policy advisor in the White House Office of National AIDS Policy, where he helped author President Obama’s original National HIV/AIDS Strategy and worked to support the strategy’s implementation across the federal government.

Greg also serves as a member of several advisory boards, including the HIV Prevention Trials Network and the CDC/HRSA Advisory Board.

His work on health disparities has been published in top medical, public health, and policy journals. And his research assessing the impact of COVID-19 among Black and Latino Americans was the first national study published on COVID-19 infection disparities. And his expertise on HIV disparities has been featured in Time magazine, The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Wall Street Journal.

About Glen Pietrandoni

Glen is chief advocacy officer at Avita Care Solutions, an award-winning pharmacy leader, passionate 340B program advocate, and internationally respected HIV and LGBTQ+ activist. He’s deeply engaged in Avita’s mission to advocate for health equity and the 340B Drug Pricing program and works to bring together stakeholders from the pharmaceutical industry and patient advocacy arenas. Through webinars, conferences, Avita’s thought leadership blog series “The Take,” and the organization’s engagement with multiple community and trade associations, Glen leads Avita’s educational and awareness efforts and acts as a voice for its covered entity partners and patients. He continually fights for continued access to the 340B program and advances stigma-free HIV, PrEP, LGBTQ+, and sexual wellness care for underserved patient populations.

Glen recently received Pharmacy Times’ Lifetime Leadership honor at the Next-Generation Pharmacist awards. He serves on the Board of Pharmacy for the State of Illinois, was formerly chairman of the Board of Trustees of AIDS United, and sits on the board of Community Voices for 340B (CV340B). He has earned American Academy of HIV Medicine and Apexus 340B certifications.